Fashion

Why Ed Hardy Matters, Hate the Brand, Love the Man

Do you know him as Ed Hardy, the clothes designer for Facebook users who give the “rock on” salute? Or Don Ed Hardy, the century’s most influential and knowledgeable tattoo artist? Meet the latter if the former is true. Almost every tattoo you see now can be traced back to some component of his vision – for better or ill.

Wear Your Dreams: My Life in Tattoos, Hardy’s book, doesn’t convey the whole story. The book, co-written with Joel Selvin, traces the vectors of his professional life: as a child growing up in Southern California in the 1950s, he mock-tattooed his friends from the age of ten; as a teen, he visited tattoo shops in arcades on the Long Beach Pike; and as an adult, he frequented the nascent Los Angeles gallery scene in the early 1960s. Hardy studied printing at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) during the peak of the Bay Area figurative art movement, which foreshadowed his formal interest in tattooing.

He adds, “I admired artwork with a certain craft, severe demands requiring materials and procedures that had to be done a certain manner.”

Monochromatic painting, in black and white or grey tones, appealed to me. I enjoyed the dark tones the lithos could provide, as well as the fact that it was multiple originals. That appealed to me because it was democratic and anti-elitist. It was a work of popular art.

He adds, “I admired artwork that had a certain craft, severe standards requiring instruments and procedures that had to be done in a certain way.”

Monochrome art, in black and white or grey tones, appealed to me. I liked the dark tones the lithos could provide and the fact that it was a multiple original appealed to me. That was appealing to me because it was democratic and anti-elitist. It was a work of art created by the general public.

Hardy says, “I realized tattoos didn’t have to be an eagle and an anchor.” “I was aware that it was egregiously provocative.” Nobody had done it before […] However, it seems to me that it might be done in such a way that it would be a challenge as a visual art form.”

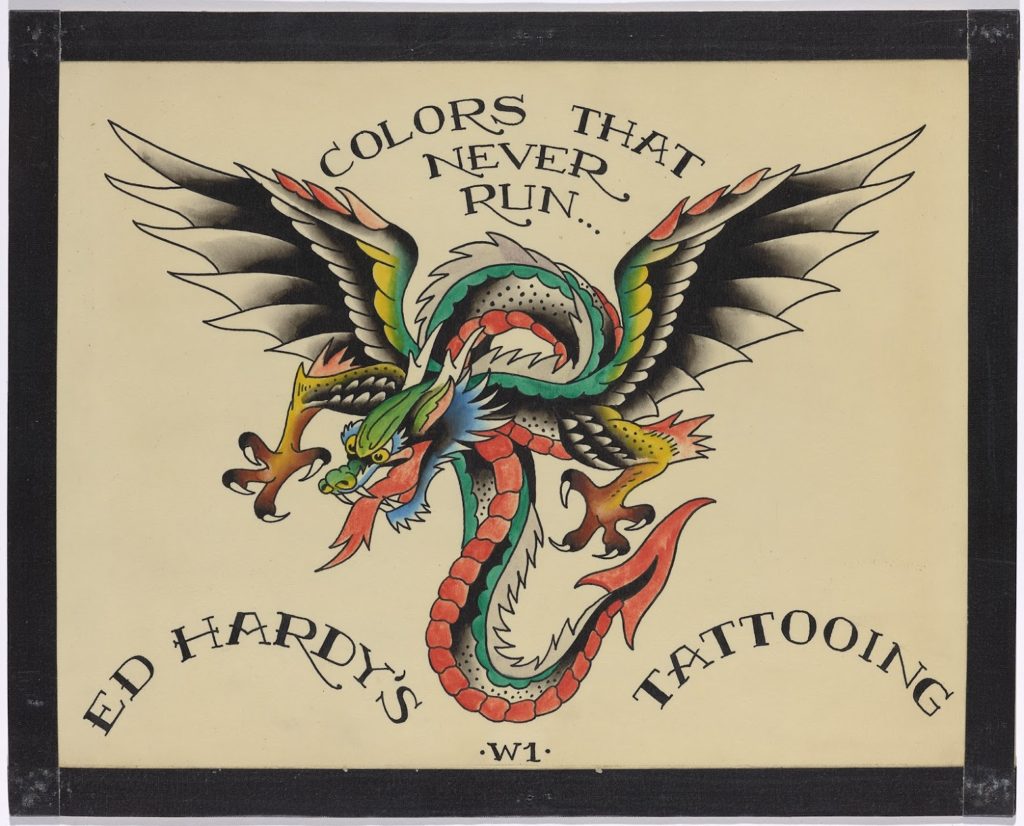

Hardy turned down a full graduate teaching fellowship at Yale after graduating in 1967 to pursue tattooing. He met and worked with Norman “Sailor Jerry” Collins, a tattoo artist from Honolulu who had acquired an interest in Asian culture during his time in the navy. Collins was noted for combining traditional American images with the bigger size, finer detail, and higher intricacy of Japanese tattooing – as well as his color experiments. He corresponded with Japanese tattoo artists and arranged for Hardy to study with Kazuo Oguri, the first Westerner to learn with a traditional Japanese master, in Japan in 1973.

Hardy returned to San Francisco a year later and founded Realistic Tattoo, the first appointment-only store dedicated to unique designs. Realistic is why today’s tattoo shops resemble art studios, galleries, or hair salons; why celebrity tattooists have waiting lists that stretch for years; why more people plan out their tattoo collections and research the best artist for a specific job; why so many art school graduates are pushing ink; and why, despite the ocean of bad skin art sloshing around the globe, the best work is becoming increasingly excellent. Search for Duke Riley (Brooklyn), Roxx TwoSpirit (San Francisco), Colin Dale (Copenhagen), Saira Hunjan (London), or Yann Black (Montreal) on the internet, then sit back and let your head tremble.

Hardy’s objective has always been to bring beautiful art and tattooing together. He states, “I intended to advance the art form”:

I brought […] a sense of art history, a deep commitment to the medium, and somewhat of a chip on my shoulder for the rest of the world who did not hold the art of tattoo in the same respect as I did.

That endeavor had been a failure until lately. For reasons involving money, class prejudice, and the difficulties of presenting human bodies, the institutional art world has shown little interest in the tattoo as design, fine art, street art, or fashion. However, there are signs of change: last year, the Honolulu Museum of Art had a display featuring 10 modern Hawaiian tattoo artists. Amund Dietzel, a famed Old School Milwaukee tattooist, has a new display at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Tattoo displays have also been shown this year at museums in Germany (the Museum Villa Rot) and Switzerland (the Gewerbemuseum).

Wear Your Dreams is a captivating narrative of Hardy’s journey, but it falls short of conveying his enormous influence — not just on tattoo art, but also on the society and conversation around it. It won’t work as a memoir. Hardy, who is known for his quiet demeanor, would never do such a thing. During a late-90s interview, I recall his astonishment when I informed him that a source had said he had orchestrated the murder of a rival tattooist who had died in a bicycle accident in Manhattan. Any other person would have been incensed. Hardy was perplexed: how could someone on the opposite side of the national plan such an event?

On a number of occasions, Hardy lifted the bar. In 1982, he and his wife, Francesca Passalacqua, founded Tattootime, a sporadic publication conceived as “a high-quality magazine that would reflect well on the intellectual grounding of this new tattoo movement, without being stuffy,” he writes in Wear Your Dreams, without going into further detail. The now-defunct five-issue series is a goldmine of oral and reported history (I’ll never forget reading tattooist Bob Shaw’s story about a female scratcher who agreed to remove a GI’s tattoo by pouring acid on his chest and letting it burn through a half-inch of flesh in 1951), as well as a kind of ongoing public distillation of the state of the art through the 1980s and ’90s — a time when there was little design-literate writing

Most Tattootime pieces gave a friendly insider’s tour of the business, while others dug the past, recording trade procedures from mixing and applying colors to building and balancing machinery. Tattooing in Borneo and Samoa, as well as the rising tribal traditions in the United States that were so popular in the 1990s, were addressed in a 1982 issue titled “New Tribalism.” Hardy summarises the predicament of the modern American artist in it:

Today’s tattoo artist is caught up in a cultural jumble. For many segments of society serviced, the designs (value systems) established and peddled as stock in trade during the previous hundred years have grown unsuitable or outmoded. The growing popularity of this form of expression among a broader spectrum of individuals has necessitated the creation of new images and the hiring of more skilled stylists.

That’s precisely what Hardy and an expanding network of like-minded mavericks delivered.

According to a story in the 1991 edition of Tattootime,

The abstract nature of the backdrop parts that frame and unite the topics of the mural style body pieces is a key part of the attractiveness of the Japanese heritage. We’ve seen that the client’s desire to make it ‘look Japanese’ through the use of what has become known as ‘wind bars,’ ‘finger waves,’ and other techniques often takes precedence over the core topic matter.

The present tattoo renaissance is defined by its attention to location and overall body composition. (I was walking to the bank in my little Hudson River town yesterday when I came across a young woman with a half-sleeve tattoo of exquisite Hokusai-like waves spilling down her upper arm.) Ed Hardy, hello!)

Tattootime’s devotion to following trends and dissecting procedures is notably lacking from today’s slew of tattoo publications, which are almost entirely focused on imagery and the backstories that inspire it but offer little formal critique. Tattoo reality shows like NY Ink are all about the backstory; they revolve around the tedious tales of love and loss, the trauma and drama surrounding the tattoo, but the vocabulary surrounding the art itself is devoid, ranging from the affirmative “Cool!” to the inevitable “Oh my God!” that serves as a critical reaction to the completed piece.

Shows that compete do better. I always enjoy the few minutes at the end of Best Ink and Ink Master when the judges critique the work of the competing tattooists, expounding (always too briefly) on technical considerations such as shading, highlights, scale, perspective, line strength and consistency, color combinations, light source logic, and adherence to conventions such as pinup positioning. It’s a learning experience. The judges’ indifference (or blindness?) to the insistently absurd visuals under consideration dampens the experience: pastel animals, Star Wars sceneries, and, in one mind-boggling episode, a Manhattan skyline made of bacon. If the concept were the only criterion, everyone would be eliminated after the first challenge.

In 1995, Hardy organized the first large-scale gallery exhibition of tattoo art, “Pierced Hearts and True Love: A Century of Drawings for Tattoos,” at the Drawing Center in New York, which drew large crowds and launched the career of Dr. Lakra, one of the few tattooists to gain purchase in the blue-chip art world. Freddy Negrete, who took exquisite black and grey fine line tattooing from jail to the public, and Leo Zulueta, who popularised neo-tribal tattooing, were both pioneering artists who Hardy supported and nurtured. Since the early 1980s, when California artist Jamie Summers worked in his shop and New Mexico artist Cynthia Witkin was featured in his magazine, he has promoted emerging artists, including women. (Full disclosure: he wrote a blurb for my book Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo, which came out in 1997.)

Hardy has also made insightful observations about the sociology of tattoos. “Tattoos usually tell you more about the people looking at them than the person wearing them,” he told RE/Search magazine in 1989, echoing a tattooist in Sarah Hall’s excellent novel, The Electronic Michelangelo: “I’ll tell you something, lad: A tattoo says more about the person who is staring at it than the one who has it on his back.” He considers tattoos as a form of visual supplement to oral history — “the story’s flashcard.” “You can only truly understand the tattoo by getting to know the person who is wearing it,” he has remarked. Tattoos serve as markers or valves for their mind.”

Many Hardy fans, including myself, were perplexed by the rapid influx of Hardy items into retailers in the mid-2000s, as was Hardy himself. When Hardy was approached by Christian Audigier in 2004 about licensing his classic American designs, he did some study on the French designer and came to the conclusion, “This guy is at ground zero of everything that is wrong with current culture.” But Hardy came on with the intention of making a little money; he had no idea that his name would become the catalyst for a $700 million-a-year industry based on tattoo nostalgia. Hardy denied Audigier’s offer of global travel, press conferences, and a Bentley since he had no stake in the business: “I just wanted to be paid and be left alone.”

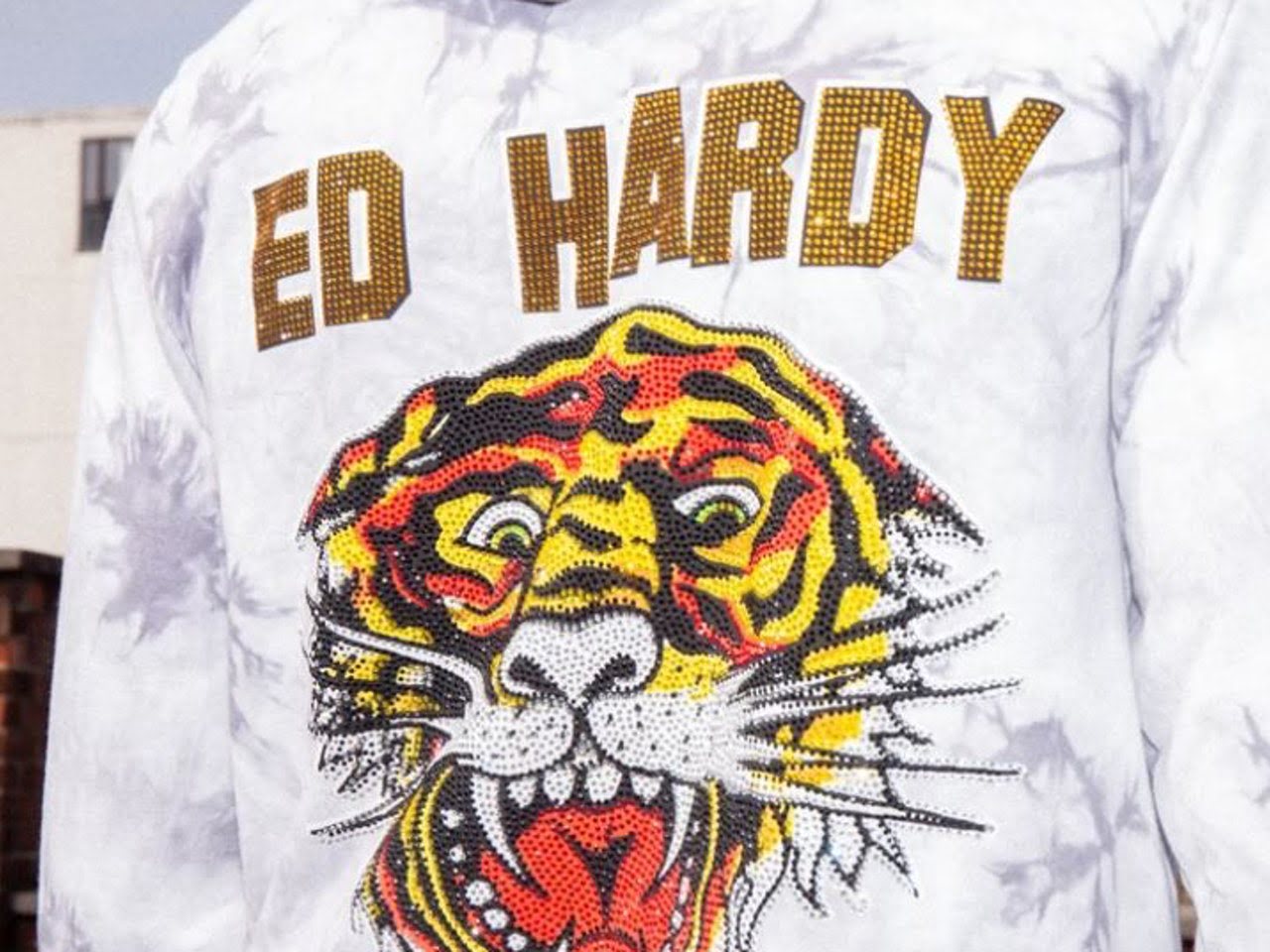

He walked into the first Ed Hardy store in Los Angeles a few weeks later, wearing a grey cardigan and a $10 Timex watch, and was greeted like a “square, old guy,” took one look at the blingy sales crew, and knew, “These were not my people […] I began to understand where this was headed.” His life would soon be colored by an embarrassment of Ed Hardy shower curtains, tanning creams, baby clothing, and golf carts.

Surprisingly, the Hardy brand made a man who deserved to be renowned for all the wrong reasons popular. It borrows from his earlier work, which he sought to transform into something broader and artistically minded. He writes in Wear Your Dreams, ”

I believe I have a good understanding of what Christian observed in the designs. They were supposed to be symbolic, like heraldry. They’re bold – the objective of traditional Western tattoo designs is that they stand out on the flesh. Heavy shading, dark and bright values, and a form silhouette that is easily recognized.

“These objects are distillations of human desires and hopes,” he adds, whether it’s a dagger, a heart, or a panther. They also stand for something. This represents me […] in a tiny but significant manner.”

Emblems that hug the body, on the other hand, look bad on hoodies – and much worse on trucker caps. When taken apart of context, the tattoos resemble billboards. The brand took a medium founded in personal expression, slathered it with glitter and studs, and repeatedly reproduced it, turning it into everything a tattoo isn’t.

Many people despised it, yet it was purchased by a large number of individuals, including celebrities. Hating Ed Hardy has become a national pastime, as seen by the several articles in the Urban Dictionary dedicated to him:

BMER/BENZ driving club youngsters who still live at home use it as a status symbol. Cougar MILFS can be spotted wearing it while connecting with their psychopath offspring at the mall.

A method for all the douchebags in the world to declare, “I’m unique.”

College frat guy douchebags, Guidos, and other steroid-addicted muscle head virtually exclusively wear it.

In 2009, the website “Stuff White People Like” published an article titled “Hating Ed Hardy,” in which the author joked:

White folks despise Ed Hardy [clothing], therefore it can’t be worn humorously. This is no easy task. Nazi uniforms, Ku Klux Klan robes, and self-tanner are currently the only other items in this category.

Audigier sold the Ed Hardy brand two years later, and Hardy recovered some control over the designs. However, the harm had already been done. Hardy’s brand eclipsed his creative legacy, unlike Lou Reed, who long ago began licensing his music for auto commercials, or Damien Hirst, whose merchandising has included $2,000 skateboard boards and Louis Vuitton bags.

Many people believe Hardy is a fictional character like Betty Crocker, a historical figure like Captain Morgan, or a figure from the surf culture — like Von Dutch, aka Kenny Howard, the custom car pinstriper whose daughters sold his nickname in 1999 after his death, launching yet another wildly successful brand — thanks to Audigier. Few people recognize him as an artist and cultural disruptor. Many tattooists could learn something from the man who, in his formative years, inhaled art history, read the Beats, and soaked up cool jazz, and whose idea of fun was spending an afternoon in a museum with fellow pioneer Mike Malone covertly photographing the Utagawa Kuniyoshi prints that “became the key reference base for us to work with.”

If the Hardy series made him famous and notorious by tying this lover of craft to a vulgar and artless “product,” it also allowed him to return to printing financially. Tattooing is not only technically challenging — requiring the use of heavy, fussy equipment to draw on an untamed canvas draped across a customer who will both dictate the design and wear it for the rest of their lives — but it is also physically demanding. Due to arthritis, Hardy has had problems with his hips (both of which have been replaced) and hands. Inked magazine recently quoted him as saying:

With this entire brand thing falling on my head, the one good thing that happened was that I didn’t have to rely on tattooing as a source of revenue […] It also reintroduced me to my own personal work, which was a revelation.

He ceased tattooing in 2008 and has been creating and presenting prints in his San Francisco store, as well as instructing tattooists.

The narrative of Ed Hardy is best understood as a California allegory of unwavering self-invention. “With my bad-boy surfer mates who didn’t know or care anything about art, I was alone as a youngster,” he adds. Born into the surf and custom car subcultures; attuned to Southern California’s sunshine and noir binary (“I was drawn to dark stuff”); inspired by Ferus Gallery artists, several of whom were taken with the surface beauty of auto bodies; educated at the famously bohemian SFAI, which blurred the lines between fine and applied art; and in step with California Conceptualism in its embrace of the unconventional, often ephemeral (sometimes corporeal) medium. He not only opened up the aesthetic potential of Western tattooing by freeing it from its ingrained folk language, but he also positioned this “people’s art” as a direct challenge to the commodity-driven, hyperinflated art market.

“My whole life has been a balance between traditional formal education — both in terms of the tools of a medium and the history and philosophy of art,” he previously told The Believer, “and its resonance in the visual culture of our daily lives.”

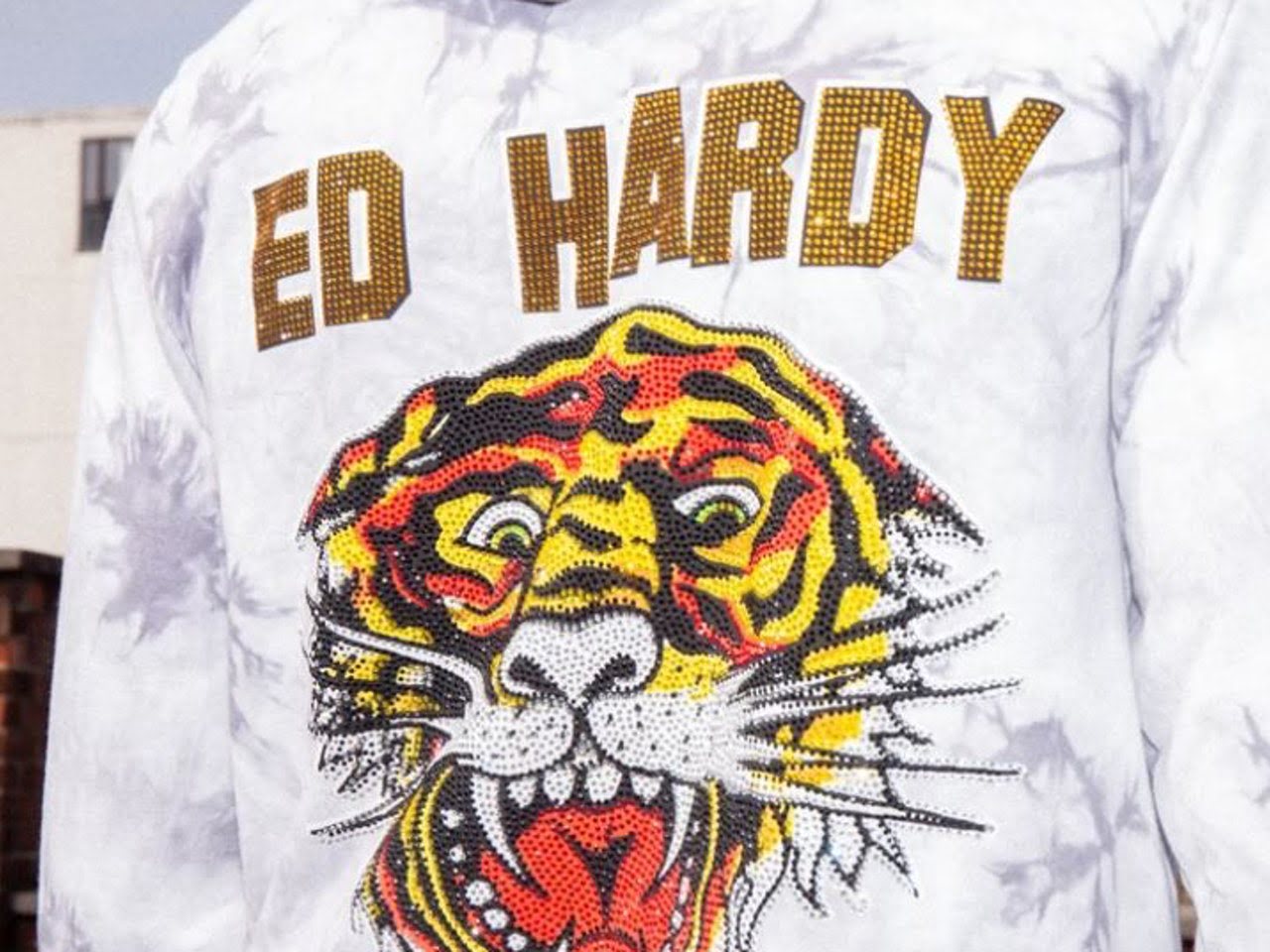

Ed Hardy’s New Line Honors Tattoo Culture and Graphics

Ed Hardy was renowned as a true American artist before bringing his creativity into the domain of fashion. He helped usher in the contemporary era of tattoo style before branching out into super-heavy designs on apparel. Ed Hardy wanted to translate his expressive art form into fashion with his namesake clothes and accessories line by making items with tattoo-inspired motifs, meaningful design, and incorporating it into the company DNA. Ed Hardy has weathered the test of time by using apparel to promote a culture of inventiveness and unashamed uniqueness. Now, the label is attempting to increase its impact by releasing a new collection that focuses on bringing the art form’s real origins into the larger cultural debate.

CLICK HERE: FOR MORE READING ABOUT UPDATED TIME

The brand’s current collection honors the renowned artist’s body of work and unmistakable impact by patching them onto a variety of graphic T-shirts, tracksuits, printed woven shirts, hoodies, leather jackets, and embroidered denim jackets. In addition, another tier of the collection has Ed Hardy’s high-end “By Appointment Only” line, which features handmade, hand-painted products. Hardy’s own experiences creating the company over the previous fifteen years inspired this moniker, including a period in his career when military guys started turning up inebriated to his shop and falling asleep all over the place. Hardy and his partner determined that it should be “by appointment only” from then on. Weaving these narratives into his collections is what has made Ed Hardy so unique, while also elevating the brand to the point where it has become part of a worldwide community of passionate people who aren’t hesitant to express their own stories. Footwear, backpacks, loungewear, swimwear, outerwear, fragrance, and liquor will all be included in this new collection.

The Ed Hardy collection is now available on the brand’s website for purchase.

Fashion

Angelicatlol Facial: The Secret to Radiant, Youthful Skin

Table of Contents

The Angelicatlol Facial is quickly becoming a favorite in the world of skincare. This cutting-edge treatment combines advanced techniques with high-quality ingredients to give your skin a radiant and youthful appearance. Whether you want to fight aging, improve skin texture, or simply indulge in a luxurious experience, the Angelicatlol Facial promises to deliver visible results.

Why is it so popular?

People love this facial because it caters to a variety of skin concerns, offering deep hydration, improved skin tone, and noticeable rejuvenation. It’s suitable for anyone looking to refresh their complexion with a treatment that feels as relaxing as it is effective.

Key Features of the Angelicatlol Facial

Advanced Skincare Techniques

The Angelicatlol Facial is all about using cutting-edge methods for maximum effectiveness. These may include microcurrent technology, light therapy, or gentle exfoliation, each designed to improve circulation, tighten skin, and promote collagen production.

Premium Ingredients for Deep Nourishment

This facial doesn’t just rely on traditional methods. It uses luxurious skincare products packed with ingredients like hyaluronic acid, vitamin C, and botanical extracts, all carefully selected to nourish and hydrate the skin deeply. These ingredients help achieve a youthful, glowing complexion.

Customizable Treatment

Everyone’s skin is unique, and the Angelicatlol Facial understands this. The treatment is customizable based on your skin type and specific concerns. Whether you have dry skin, acne, or signs of aging, the facial can be tailored to target exactly what your skin needs.

Step-by-Step Process of the Angelicatlol Facial

a) Pre-Facial Preparation

The treatment begins with a thorough cleansing to remove any makeup, dirt, and impurities. A quick skin assessment is done by a skincare expert, who will then choose the best approach for your specific skin needs.

b) Deep Cleansing and Exfoliation

Next, a gentle exfoliation process is done to remove dead skin cells and unblock pores. This can be done with enzyme treatments or a mild exfoliant, followed by steam to open the pores for deeper cleansing.

c) Nourishment & Hydration

After cleansing, serums packed with antioxidants and hydrating ingredients are applied to rejuvenate and deeply hydrate your skin. Special masks might also be used to lock in moisture and refresh your skin.

d) Skin Rejuvenation Techniques

To take things a step further, the facial may include light therapy (which helps with skin repair and collagen production) or a gentle facial massage to improve circulation. These techniques aim to firm and brighten the skin.

e) Final Touches & Protection

To finish, your skin is treated with a nourishing moisturizer and a layer of SPF to protect your skin from harmful UV rays. The final steps ensure your skin stays smooth, hydrated, and protected after the treatment.

Key Benefits of the Angelicatlol Facial

The Angelicatlol Facial is designed to tackle multiple skin concerns at once, offering a wide range of benefits:

- Hydration: Your skin will feel deeply moisturized, with a healthy glow.

- Skin Brightening: Ingredients like vitamin C help lighten dark spots and even out your skin tone.

- Anti-aging: Regular sessions can reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles.

- Improved Texture: With gentle exfoliation and rejuvenation, the facial can smooth out rough patches, leaving your skin feeling soft and refreshed.

Who Should Try the Angelicatlol Facial?

The Angelicatlol Facial is suitable for all skin types, including sensitive, oily, and dry skin. It’s especially beneficial for:

- Those dealing with dullness or uneven skin tone.

- Anyone looking to fight signs of aging, such as wrinkles or fine lines.

- People with acne or blemishes, as it helps cleanse and refresh the skin.

Ingredients Commonly Used in the Angelicatlol Facial

This facial uses some of the best ingredients to nourish and rejuvenate your skin:

- Hyaluronic Acid: Known for its ability to draw moisture into the skin, keeping it plump and hydrated.

- Vitamin C: A potent antioxidant that minimizes aging signs and brightens the skin.

- Peptides: Enhance skin elasticity and firmness by promoting the generation of collagen.

- Botanical Extracts: Natural plant-based ingredients that soothe and heal the skin.

Aftercare Tips for Best Results

To maintain the glowing results of your Angelicatlol Facial, here are some aftercare tips:

- Avoid harsh exfoliation for a few days to prevent irritation.

- Stay hydrated by drinking plenty of water to help your skin stay moisturized.

- Use SPF at all times to shield your skin from UV rays.

- Follow a gentle skincare routine to keep your skin nourished.

Comparison with Other Popular Facials

While there are many facial treatments available, the Angelicatlol Facial stands out for its combination of advanced techniques and luxurious ingredients. It’s more comprehensive than basic facials and provides a deeper level of skin rejuvenation. Unlike treatments such as chemical peels or hydrafacials, which focus on specific issues, the Angelicatlol Facial addresses multiple concerns at once.

Conclusion

The Angelicatlol Facial is more than just a skincare treatment—it’s a complete rejuvenation experience. With its blend of advanced techniques and high-quality ingredients, it can help achieve glowing, hydrated, and youthful skin. Whether you’re looking to treat acne, fight aging, or simply pamper your skin, the Angelicatlol Facial could be the perfect choice for you.

FAQs

Can I wear makeup after the Angelicatlol Facial?

It’s best to wait at least 24 hours to allow your skin to fully absorb the benefits and avoid clogging pores.

Does the Angelicatlol Facial cause any redness or irritation?

Most people experience minimal to no redness, but those with sensitive skin might have slight flushing that fades quickly.

Is this facial safe for pregnant women?

Yes, but always check with your doctor, and ask the esthetician to avoid strong active ingredients like retinol.

How soon can I see results after the facial?

You’ll notice an instant glow and smoother texture, with even better results after a few days as your skin absorbs the nutrients.

Can men benefit from the Angelicatlol Facial?

Absolutely! It helps with hydration, breakouts, and ingrown hairs, making it great for all skin types, including men’s skin.

Beauty

Via Max – Sense TZE Active Gel Estimation: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

Skincare is an essential part of maintaining healthy, youthful-looking skin, and using the right products can make all the difference. One such product gaining popularity is the Via Max – Sense TZE Active Gel Estimation, designed to provide intense hydration, healing, and anti-aging benefits. This article explores everything you need to know about this gel, from its features and benefits to its application and value.

Product Overview

The Via Max – Sense TZE Active Gel Estimation is a lightweight, non-greasy product that addresses various skin concerns. It combines effective natural and scientifically proven ingredients to nourish, heal, and rejuvenate the skin.

- Main Features:

- Hydrates and locks in moisture.

- Soothes and repairs irritated skin.

- Boosts collagen for firmer, youthful skin.

- Suitable for all skin types, including sensitive skin.

- Key Ingredients:

- Aloe Vera: Known for its soothing properties, Aloe Vera reduces redness and calms inflammation.

- Tea Tree Oil: Helps combat acne with its antibacterial and antifungal properties.

- Hyaluronic Acid: A powerful humectant that retains moisture, leaving skin plump and hydrated.

- Vitamin E: Protects against environmental damage and supports skin repair.

Benefits of Using Via Max – Sense TZE Active Gel Estimation

- Deep Hydration:

- Keeps skin moisturized throughout the day.

- Prevents dryness and flakiness, especially in colder months.

- Healing Properties:

- Aids in soothing irritated skin caused by environmental factors or skin conditions.

- Reduces redness and inflammation.

- Anti-Aging Effects:

- Promotes collagen production, which helps reduce fine lines and wrinkles.

- Restores skin elasticity for a youthful appearance.

- Enhanced Skin Texture:

- Smoothens rough patches and evens out skin tone.

- Leaves skin feeling soft and supple.

Usage Instructions

To achieve the best results, follow these steps:

- Cleanse:

- Start with a clean face to remove dirt and oil.

- Apply Gel:

- Take a small amount (pea-sized) and spread evenly across your face and neck.

- Massage:

- Gently massage until fully absorbed.

- Frequency:

- Use twice daily, preferably in the morning and evening.

Precautions:

- Avoid direct contact with eyes.

- Conduct a patch test on a small area of skin before full use, especially if you have sensitive skin.

Product Estimation

- Cost Analysis:

- The gel typically comes in a 50ml container and is competitively priced compared to similar products.

- The price reflects its premium ingredients and proven benefits.

- Value for Money:

- The long-lasting effects make it a cost-effective option.

- A little goes a long way, as only a small amount is needed per application.

- Availability:

- The product is readily available online through platforms like Amazon and select retail stores.

Customer Reviews and Feedback

- Positive Reviews:

- Many users have praised its lightweight formula, noting how quickly it absorbs without leaving a greasy residue.

- Users report visible improvements in hydration and reduction of fine lines after consistent use.

- Concerns:

- Some users found it less effective for severe skin conditions like eczema or rosacea.

- A few mentioned the price as slightly higher than budget-friendly alternatives.

Scientific Backing

- Aloe Vera: Proven to reduce skin inflammation and irritation.

- Tea Tree Oil: Supported by studies for its antimicrobial properties, beneficial for acne-prone skin.

- Hyaluronic Acid: Widely recognized for its ability to hold water up to 1,000 times its weight.

- Vitamin E: Known for its antioxidant effects, protecting skin cells from oxidative damage.

These ingredients work synergistically to deliver optimal skincare results.

Comparison with Other Products

When compared to similar products, Via Max – Sense TZE Active Gel Estimation stands out due to its unique combination of ingredients that address multiple skin concerns. While some competitors may focus solely on hydration or anti-aging, this gel delivers both, along with healing properties.

Final Thoughts and Recommendations

The Via Max – Sense TZE Active Gel Estimation is a versatile skincare product suitable for individuals looking to improve hydration, reduce signs of aging, and enhance skin texture. Its lightweight, non-greasy formula makes it ideal for daily use, regardless of skin type.

Call to Action

If you’re seeking an all-in-one solution for your skincare routine, consider adding the Via Max – Sense TZE Active Gel Estimation to your lineup. You can purchase it online or from trusted retailers. For optimal results, maintain a consistent skincare routine and consult a dermatologist if you have specific concerns. Your skin deserves the best care!

Article Recommendations

8882381346: Dealing with Spam and Scam Calls

816-608-8691 Contact Details and Usage Guide

All You Need to Know About DMC001881: The Versatile Lug Nut Cover

Fashion

The Rise of Collector Shoes: How a Niche Hobby Became Mainstream

Table of Contents

Ever wondered how sneakers leapt from gym floors to high-fashion runways? What started as a niche interest for a small community has exploded into a global phenomenon.

Today, the sneaker collection has become a multi-billion dollar industry. Dedicated collectors and enthusiasts spend hours and thousands of dollars on their beloved shoes. But how did this all start?

Join us as we lace up and jump into the colorful world of collector shoes, where every pair tells a story. Let’s explore!

The Intersection of Sneakers and Hip-Hop Culture

The rise of collector shoes can be traced back to the 1980s when hip-hop and sneakers culture began intertwining. Artists like Run-DMC started sporting iconic Adidas Superstars on stage, sparking a trend among their fans.

Sneakers became more than just footwear. They became a statement of personal style and cultural identity. This connection between sneakers and hip-hop culture laid the foundation for what was to come.

The Role of Limited Editions and Sneaker Drops

The introduction of LE releases and sneaker drops further fueled the collector shoe market. Brands began producing shoes in limited quantities, creating a sense of urgency and exclusivity among collectors.

Sneaker drops also became events, with people camping out for days to get their hands on a coveted pair. This sparked a new level of hype and demand for collector shoes, leading to increased prices and reselling culture.

The Online Sneaker Community

The rise of the internet and social media played a crucial role in the collector shoe industry. It allowed for:

- easy access to information

- worldwide connection

- buying and selling of shoes online

Platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook have created a virtual community. This is where sneaker enthusiasts can share their collections, opinions, and trade or sell their shoes.

The internet has also made it easier for resellers to access a global market, driving up the prices of rare sneakerhead shoes. This has opened up opportunities for small businesses and entrepreneurs.

The Influence of Celebrity Endorsements on Sneaker Popularity

As hip-hop grew in popularity, so did the influence of celebrities on sneaker trends. Brands began collaborating with artists, athletes, and actors.

These collaborations fueled demand among collectors and created a sense of exclusivity and rarity. For example, the partnership between Nike and Michael Jordan led to the creation of the Air Jordan series. A line that would redefine the collector shoe market.

Michael Jordan’s impact on society was undeniable. His shoes became more than just a fashion statement, they were a symbol of greatness and success.

For those looking to expand their collection or snag their next rare pair, visit novelship.com, a hub for sneaker aficionados around the globe.

The Future of Collector Shoes

As we look towards the future, it’s clear that collector shoes are here to stay. With new collaborations, limited editions, and sneaker drops happening every day, the market is constantly evolving.

Don’t miss out on the latest drops and exclusive releases. Stay connected, stay stylish, and keep expanding your sneakers collection. Happy collecting!

-

Travel4 years ago

Travel4 years agoThe Family of Kirk Passmore Issues a Statement Regarding the Missing Surfer

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoManyroon: The Key to Unlocking Future-Proof Business Solutions

-

Cryptocurrency1 year ago

Cryptocurrency1 year agoBest Tips For Cryptopronetwork com Contact 2024

-

Technology3 years ago

Technology3 years agoPaturnpiketollbyplate Login & Account Complete Guide Paturnpike.com

-

Apps & Software2 years ago

Apps & Software2 years agoFapello 2023: Social Media Platform for NSFW Content

-

Law3 years ago

Law3 years agoShould I Hire a Lawyer For My Elmiron Case?

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoCoyyn.com Gig Economy: Smart Contracts and Fair Payments for Freelancers

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoAcumen: The Key to Smart Decision-Making and Success